I've noticed that when it comes to making decisions, we often tell ourselves a story, one full of reasons that sound good but don't really get to the point. We rationalize why we want to move, switch jobs, or start something new, layering on justifications that distract from the real reason.

Table of Contents

What if we could cut through all that noise and get to the real reason? In Rework, there's a great analogy about a hot dog stand: focus on the hot dog (the core of your business) and forget the distractions. At the same time, The Happiness Hypothesis talks about our "inner lawyer," the part of us that backs up our gut feelings with a lot of random arguments.

In this post, I'll show how combining these ideas can help us simplify decision-making. It starts with one simple question: What's the hot dog? What's the one true reason driving this decision?

The "Hot Dog" from Rework: Focusing on the Core

In Rework, there's a story about a hot dog stand that really resonated with me. The idea is simple: if you're running a hot dog stand, what really matters? The hot dogs. You don't need a complicated menu, relish, or even buns. At its core, you really only need hot dogs. The rest is just extras.

Page from 'Rework' by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson of 37signals

Page from 'Rework' by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson of 37signalsI think this applies to more than just business. Whether we're making personal or professional decisions, it's easy to get distracted by all the extra details. We convince ourselves that those details are important, but they're really not. The key is to focus on what actually matters what's at the core of the decision.

The "Inner Lawyer" from The Happiness Hypothesis: How We Rationalize

In The Happiness Hypothesis, Jonathan Haidt introduces the idea of the "inner lawyer." Basically, our minds are wired to defend our gut feelings, even when those feelings aren't based on logic.

Our "inner lawyer" subconsciously comes up with reasons (generally after the fact) that justify what we already feel. It's like we're building a case for ourselves, making sure everything lines up to support the decision we've already made. The inner lawyer doesn't just justify decisions we've already made; it can just as easily construct arguments for the opposite stance, depending on what we want to believe.

Page from 'The Happiness Hypothesis' by Jonathan Haidt

Page from 'The Happiness Hypothesis' by Jonathan HaidtThe problem is, those reasons can be flimsy. We might tell ourselves we're moving for the weather or because of better job prospects, but are those the real reasons? Probably not. The inner lawyer just pulls together whatever arguments will make the choice feel more legitimate, even if they're not the core truth.

Merging the Concepts: "What's the Hot Dog?"

So how do these two ideas, Rework's "hot dog" and Haidt's "inner lawyer," come together? For me, it's about asking one question: What's the hot dog? What's the real, underlying reason behind this decision, belief, or desire?

When you strip away the justifications your inner lawyer is throwing at you, the goal is to find that one core driver, or the "hot dog".

Maybe you're thinking about moving to a new city. You start by listing all the reasons: better job opportunities, nicer weather, friends who live nearby. But when you really ask yourself, What's the hot dog? you might find that the real reason is something simpler, like just wanting a change.

This question cuts through all the noise. It's a way to get past rationalizations and focus on the one true reason driving your choice.

Examples

Let's look at how this plays out in real life.

- A friend invites you to dinner, but you don't want to go. You start thinking of excuses: you're too tired, you've got work tomorrow, maybe you don't like the restaurant. But what's the hot dog here? Maybe you're not feeling up for socializing today.

- You feel the need to own your own home. You might rattle off reasons like building equity, having a stable investment, or avoiding rent hikes. But what's the hot dog? Maybe it's having a space that feels like it's truly yours.

- You're in an unhealthy relationship, but choose to stay. You tell yourself things like "It'll get better" or "I won't find anyone better." But when you really ask, what's the hot dog? Maybe it's that you're afraid of being alone.

Using "What's the Hot Dog?" to Clarify Choices

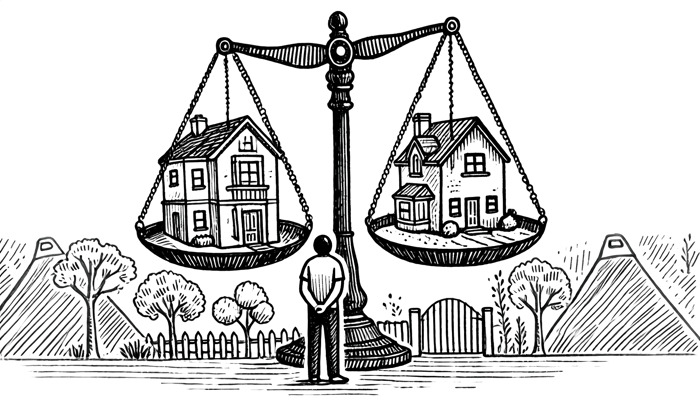

Let's dig deeper into the second example: whether to own your primary home. Once you've stripped away your inner lawyer's justifications, like building equity or avoiding rent hikes and identified that your hot dog is simply having a space that feels like yours, now you can focus on just that.

Now you can ask yourself: how do I achieve that feeling of a home that's truly mine? Your gut might tell you that owning is the only way to buy furniture, artwork, and choose paint colors. But you don't necessarily need to own a home to do that. With a longer-term lease, you could still create that same sense of ownership, decorating and settling into a place that feels like yours without the commitment of ownership.

This clarity also allows you to objectively consider the other advantages of renting. Maybe renting gives you the flexibility to move quickly if your job changes or your partner's career takes a different turn. Or you might find that avoiding the risk of having a construction project pop up next door is worth more to you than the potential of turning your home into a real estate investment. Now, instead of making the decision based on your inner lawyer's justifications, you're weighing your options against the one real reason: your hot dog.

Conclusion

Decisions can easily get lost in a mess of our inner lawyer's justifications. But asking "What's the hot dog?" cuts through all that, helping you find the core reason behind a choice, emotion, or belief.